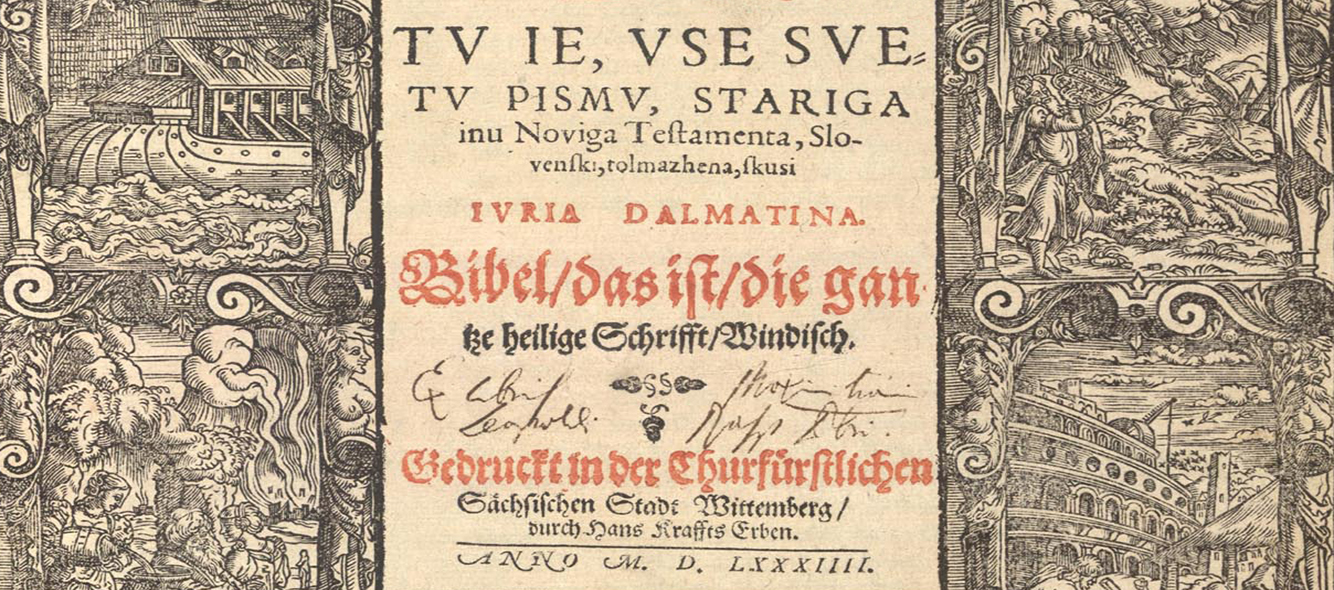

In researching a past era, a small piece of information can change a whole chain of hypotheses and conclusions. It is interesting that a misunderstanding linked to the first book printed in the Slovenian language emerged from one of these chains of hypotheses and conclusions and we only succeeded in solving it in recent years. Namely, Primož Trubar's Catechismus was not printed in Tübingen, as we had all thought up until now, but in nearby Schwäbisch Hall. There is no longer any doubt about the year of its publication: it was 1550 (and not 1551 as some had previously thought).

The "guilty party" for this interesting discovery was the German researcher Helmut Claus. In 2013, he published information in the reputable Gutenberg Yearbook (covering the history of printing) that left no doubt that the letter and initial L, found in Trubar's Catechismus and Abecedarium from 1550, was from the printing press of Peter Frentz in the town of Schwäbisch Hall. This discovery caused scholars to question the assumption made by Christian Friedrich Schnurrer in his 1799 article about Slavic-language books published in Württemberg that Tübingen, Germany was the most likely location of the printing of Trubar's first two books. Because of this assumption, it had long been believed that the printer of the two Slovenian books must have been Ulrich Morhart whose workshop printed a number of Trubar's books at a later time. Although this conclusion was logical, it was not based on any actual sources, only on Trubar's formulations from letters and introductions that suggested that he did not violate any legal prohibition when the books were printed.

Otherwise, there have always been difficulty with the sources. A number of researchers realized that, given the understanding of Trubar's statements about the year (and also the place) of the publication of Catechismus, everything was not as it should be. The available information was contradictory and researchers solved this problem over the years in various ways, always with a bit of awkwardness, since they had to overlook one or another of Trubar's statements, one or another item of actual historical proof. As indicated above, some had suggested 1551 as the year that Catechismus was published. In 1921, this seemed like the only logical explanation to France Kidrič, because he believed that the location of the publication was not in doubt. The year 1551 was moved by later researchers back to 1550 because the opinion prevailed that it would have been strange for Trubar to have given incorrect information in 1561 about Catechismus being his first book in Slovenian, providing the year of publication as 1551, while the Abecedarium indisputably had 1550 printed as the year of publication on the last page of the book.

How did we arrive to such a state of confusion? Certainly, it is in part due to Trubar's own mysteriousness about the publication that may have arose from his desire not to unwittingly implicate his printer who had done him a favour by breaking the law. But let's go through the elements that led to this confusion one by one. Twice in 1557 and then again in 1561, Trubar wrote that during the interim period when there were greater restrictions, the printing of his books in the Slovenian language had been strictly forbidden in two regions, and that he had to have them printed secretly and "with danger", and also in his absence. But why would the printing take place "with danger" ("mit gfar"), if it took place in Tübingen with the implicit or explicit approval of the Duke (or future Duke) Christoph? Now that we know that the printing took place in Schwäbisch Hall, this bit of confusion no longer arises. The main conclusion that follows from this single fact, that the books were printed in Schwäbisch Hall, is that they were printed illegally. The general confusion that preceded the discovery of a possible new location where the books had been printed was also caused by Trubar's statement in the introduction of the Slovenian translation of the New Testament between 1581 and 1582, which, based on the information of Tübingen as the likely city of publication, was translated from German to Slovenian as follows:

This statement has caused difficulties for all researchers as Trubar in two places stated that Catechismus was published in 1550, and in 1561, he also mentioned that Catechismus preceded Abecedarium which has the date 1550 printed on it. So what is the problem? Duke Christoph occupied the throne only after November 6, 1550 when his predecessor Ulrik died. In this case, if its printing was enabled by Duke Christoph, Catechismus would have had to have been published in 1551. From obtaining permission to the printing itself, some time would have to elapse, and Duke Christoph would certainly not have taken the time to grant permission to print Trubar's work in the first days after his coronation. The facts don't match, and it was, as noted above, France Kidrič who first noticed this. If we read Trubar's statement in the introduction to the New Testament assuming that the first Slovenian books were printed in Schwäbisch Hall, then things begin to fall into place. Namely, the Catechismus of 1550 was not included at all in the introduction. Trubar mentions only that, among other things, he also wrote "Catechismus with a triple short and exhaustive explanation"; this "triple" explanation is part of the versions of Catechismus published in 1555, 1567, and 1575, all under the patronage of Duke Christoph.

New information about the actual location of the first publication offer us a new and more understandable interpretation of Trubar's statement in the introduction:

According to the new interpretation of the above text, the printing of the two books took place in Schwäbisch Hall and was not allowed, which means that it was illegally carried out and did not belong among "the abovementioned Slovenian books", that is among the books printed in Tübingen.

My conclusion regarding the train of events connected to the printing of the two first Slovenian books is as follows: Trubar was unable to arrange for the printing of the books because of the prohibitions of censors in both Nuremburg and Schwäbisch Hall. Therefore, he made arrangements with the printer Peter Frentz (Frentius or Frentzius), and also most likely with the "Christian preacher" Mihael Grätter (also Gretter), to secretly print the books in Frentz's workshop in Schwäbisch Hall when Trubar was not present. That probably was not particularly difficult as printing presses were usually not monitored. Trubar's absence further reduced the danger that someone would notice what was going on. Moreover, if someone did find out about the project in Schwäbisch Hall (for example, the city authorities), they might even allow the secret undertaking to continue because the greatest worry was what might come from higher authorities. And when the secret printing at Schwäbisch Hall succeeded, Trubar never mentioned it anywhere because it would have been extremely incautious to inform the authorities of his own (and the printer’s) violation of the rules of the interim and the transgression of explicit prohibitions.

Translated by Erica J. Debeljak