Roughly speaking, the difference between a free and an unfree country is the following: can a citizen stand in the main square of the country's capital and loudly oppose the government's politics, in this case memory politics or the politics of history, without getting fined or even arrested? A more nuanced look reveals that there are a range of in-between cases. On the one hand, we find laws like the Austrian "Verbotsgesetz" (Prohibition Act) from 1947 that was passed in order to forbid the glorification of National Socialism in a post-Nazi state "liberated" only by the military force of the Allies. Although unimaginable in the American or British context, the law did not compromise Austrian democracy. On the other hand, we discern an authoritarian backlash in several post-communist countries following the 1989 transition to democracy whereby certain governments have attempted to codify a single sacrosanct narrative about the past, for example in Hungary's new constitution or in the much-disputed so-called Holocaust law in Poland.

The Hungarian Fidesz party led by Viktor Orbán won national elections in 2010 (its second term after 1998–2002) and remains in power today. In 2011, the ruling government included a section in the preamble to the new constitution stating that Hungary lost its "self-determination" on March 19, 1944, only regaining it on May 2, 1990. In March 1944, Germany invaded Hungary but allowed the Hungarian head of state, Miklós Horthy, to continue ruling. Thus, Horthy was in power during the period when most Hungarian Jews were deported (mainly to Auschwitz-Birkenau) by a relatively small group of Nazis assisted by the Hungarian authorities and gendarmes. Horthy also possessed the authority to halt the deportations of the well-integrated Jews of Budapest. The preamble to the new constitution not only absolves Horthy and the Hungarian authorities of responsibility for the Holocaust, but also externalizes to foreign powers responsibility for state persecution conducted during the postwar communist/socialist era.

In Poland, the Law and Justice Party (PiS) led by Jarosław Kaczyński won national elections in 2015 (its second term after the 2005–2007 government) and remains in power today. Already during its first mandate, PiS had attempted to regulate the politics of the past by law. In response to Jan T. Gross's book about the July 1941 mass murder of Jews perpetrated by their Polish neighbors in the village of Jedwabne, PiS passed an amendment to the Penal Code in 2006 stipulating that accusing the Polish nation of participation in, organization of, or responsibility for communist or Nazi crimes would be punishable by up to three years in prison. Luckily – and I am convinced that no scholarly quasi-neutrality applies here – the Polish constitutional court struck down the law in 2008 during a time when democratic checks and balances were still functioning in Poland.

During the second PiS mandate, an amendment to the 1998 Act on the Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation was passed, stating that "whoever claims, publicly and contrary to the facts, that the Polish Nation or the Republic of Poland is responsible or co-responsible for Nazi crimes committed by the Third Reich […], or whoever otherwise grossly diminishes the responsibility of the true perpetrators of said crimes – shall be liable to a fine or imprisonment for up to three years." Following domestic and international criticism, the criminal sanctions were reduced to civil ones, but nevertheless PiS had succeeded in its effort to dictate the terms of history: specifically what can and cannot be said about the Poles as collaborators.

These tendencies can also be found, albeit in weaker form, in other post-Communist countries. In Croatia, the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) that ruled the country under President Franjo Tuđman from 1990 to 1999 and again from 2003 to 2009, won national elections in 2015. Its first months in power created the impression that Croatia was following the lead of Fidesz in Hungary and PiS in Poland: namely, attacking democratic principles, evoking anti-European sentiments, and only half-heartedly concealing its historical revisionism. In January 2016, Zlatko Hasanbegović, known for his historical revisionist views, became the Minister of Culture and was thus in charge of the Jasenovac memorial complex at the former Ustaša death camp one hundred kilometres southeast of Zagreb. Hasanbegović, a former Vice President of the Honorary Bleiburg Platoon (Počasni bleiburški vod), pushed for the re-establishment of the parliament's patronage of the annual commemoration in Bleiburg which the previous social democratic government had ended. At the same time, he argued that the state's support for the annual commemoration in Jasenovac was a "problem". He claimed that "it is not about the commemoration of the victims or the condemnation of perpetrators, but it is misused for the rehabilitation of Yugoslav communism". Yet, in the Croatian case, this HDZ government did not have enough time to enforce their historical revisionism by law. After a no-confidence vote against the prime minister, considered a marionette of HDZ party leader Tomislav Karamarko, new parliamentary elections were held in September 2016. The results saw the same parties forming a coalition but one that did not call democratic principles into question and had more Europe-friendly faces in the cabinet. The new government is led by HDZ Prime Minister Andrej Plenković and Hasanbegović is nowhere to be seen. The Croatian case shows that the danger of authoritarian backlash is by no means limited to Hungary and Poland, the two countries against which the EU has initiated Article 7 procedures for a serious breach of basic EU values by member states.

What Orbán, Kaczyński, and Hasenbegović have in common is that they are "mnemonic warriors" – a term coined by Michael Bernhard and Jan Kubik. In contrast to "mnemonic pluralists" and "mnemonic abnegators", mnemonic warriors draw a sharp line between themselves as proprietors of the "true" vision of the past and other actors who cultivate "wrong" or "false" versions of history. To politicians who are mnemonic warriors, collective memory is non-negotiable. The meaning of events is determined by their relationship to a "golden era" of national preeminence. Mnemonic warriors claim that the problems of the present (and the future) cannot be effectively addressed until the whole polity is set on the proper foundation, constructed according to the "true" vision of history. Alternative narratives of the past are by definition seen as distorted and therefore must be delegitimized and those who believe them ostracized.

While in power, PiS and Fidesz are attempting to enforce their mnemonic regimes. These parties share certain characteristics. One is that both former Polish President Lech Kaczyński (the Kaczyński twin who died in the 2010 plane crash) and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán participated in the transformation of 1989 and believed that it should have been a decisive turning point. Yet both Fidesz and PiS consider the 1989 Round Table Agreements to have been "rotten deals" that resulted in "unfinished", "corrupt", or "stolen" revolutions or processes of democratization, as Bernhard and Kubik have pointed out. Therefore, the mnemonic warriors have initiated memory wars against the "pseudo-transition" that failed to sweep away the socialists or provide "moral clarity". PiS calls this polityka historyczna, a politics of history defined not as the analytical concepts most scholars use, but rather as a warrior's undertaking: in other words, a weaponized term.

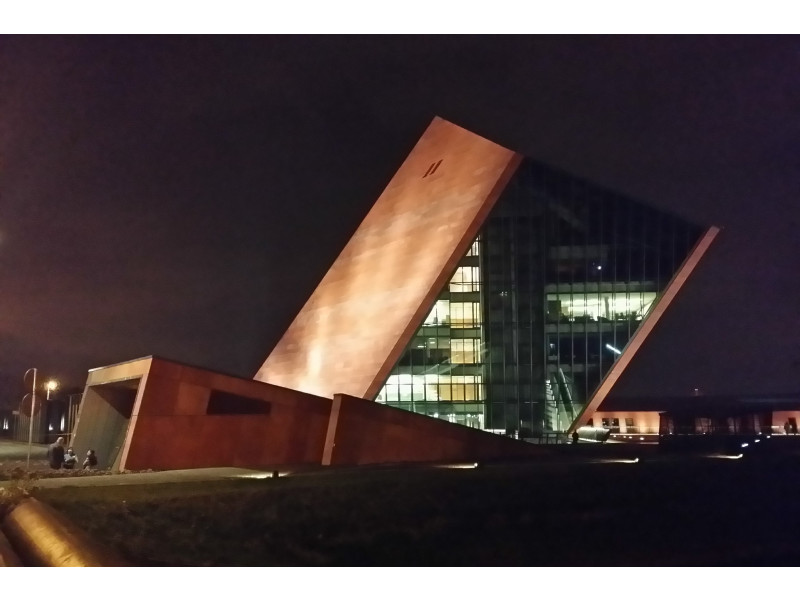

Removing representations of the past that challenge their "patriotic" narratives is one of the first tasks of mnemonic warriors when they take charge. Already in 2013, as an opposition politician, Jarosław Kaczyński attacked the concept of the yet to be opened Museum of the Second World War in Gdańsk that had been initiated by Donald Tusk of the Civic Platform (PO). Kaczyński stated: "We will defend Polish interests, Polish truth. We will reshape the Museum of the Second World War so that the exhibition in the museum shows the Polish perspective." The education of young Poles should reflect pride and dignity, "not shame" as Kaczyński claimed it had thus far. The museum opened in 2017 but was taken over by PiS and changed significantly. A prominent new exhibit in the Holocaust section now shows the Polish Ulma family murdered by the Nazis for trying to rescue Jews.

It is absolutely clear that such rescuers are necessary for a complete picture of the Holocaust, but it is equally clear that they are currently being used in Polish and Hungarian memory politics for the de-Holocaustization of the Holocaust as Elżbieta Janicka, Polish studies expert, labelled this trend. First, the preferred method is that the rescuers are named and represented by private photographs and emotional stories that evoke empathy, while the names, photographs, and stories of the Jews they were hiding are – although documented elsewhere – omitted. The memory of the Holocaust is conceived as threatening for the narrative of "our own" suffering, either under the Nazis or under Communism. Second, "our suffering" is depicted in a way that presents "us" as the real victims of a holocaust. Third, "our" perpetratorship and collaboration is omitted. Even talking about it can be sanctioned by law as the Polish case shows. Collaboration with Nazis may also be rationalized, for example, as a legitimate part of the fight against the Communist threat. Participation in the Communist regime can be overwritten by its demonization after the "nationalist turn" of the participating person or party after 1989.

Several of the trends described here are typical not only in Poland and Hungary, but these two countries have taken them farther by limiting freedom of speech and attempting to monopolize the media. Again, a broad spectrum exists between shouting out your understanding of the past in the main square and being arrested for it. In the process of the integration of post-communist countries into the EU, the memory of traumatic pasts has been canonized and transformed in a way that contributes to the – always political, disputed, and hierarchical – formation of a European space of communication and memorial landscape. In recent years, an anti-European and undemocratic spirit has been gaining ground – and the mnemonic warriors are the ones who have spearheaded this spirit.

-

1 / 3 Commemoration at the Jasenovac Memorial in Croatia, photo: Ljiljana Radonić

-

2 / 3 Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk, photo: Ljiljana Radonić

2 / 3 Museum of the Second World War in Gdansk, photo: Ljiljana Radonić

-

3 / 3 Memorial for the Victims of German Occupation in Budapest, photo: Ljiljana Radonić

3 / 3 Memorial for the Victims of German Occupation in Budapest, photo: Ljiljana Radonić

* This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (GMM - grant agreement No 816784).