Imagine a town where a kind scientist can invent a device to fix any problem – from pollution to postal delays. This is Balthazartown, the world of Professor Balthazar, a Yugoslav animated television series from the 1960s and 1970s that taught lessons about science, innovation, and social responsibility. Today, this whimsical historical cartoon remains relevant to many contemporary issues such as citizen science, the ethics of automation, and science for the public good to name only a few. A close analysis of the cartoon reveals additional layers of meaning that would also merit academic attention, for example how it reflects the values of Yugoslav socialism and subtly contrasts these with other socio-political models of science and innovation. This is of particular interest as Professor Balthazar remains present in cultural programming, national curriculum, and educational initiatives in Croatia. According to Udruga Profesor Baltazar, the educational association that aims to preserve the cartoon character, the show also has "a strong global appeal" and experienced "considerable success" internationally, notably in Scandinavia, Italy, Germany, France, Portugal, Iran, Australia and New Zealand. A new 13-episode animated series and computer game currently in development have the potential to further enhance the series' contemporary relevance.

The series was created by Academy Award nominee Zlatko Grgić, and it ran for fifty-nine episodes spread over four seasons. Professor Balthazar was produced by the Zagreb Film studio between 1967 and 1977 during what is often called the golden age of the internationally renowned Zagreb School of Animated Film. In 2021, the series was praised in CartoonBrew news and insights site for being "attuned to the creative milieu of the sixties' art world" as well as for "the simple, loosely drawn characters" that give it mainstream appeal. The piece described the cartoon as "far-out 1960s psychedelia" and concluded that its "lasting popularity" decades later "is testament to Grgić and company's inventive approach to the series". Despite the series' success, there has been limited academic discussion of how it represents science and innovation. This article aims to highlight this underexplored aspect, and, more specifically, its humanist and socially-oriented approach to science and technology.

Science for the Community

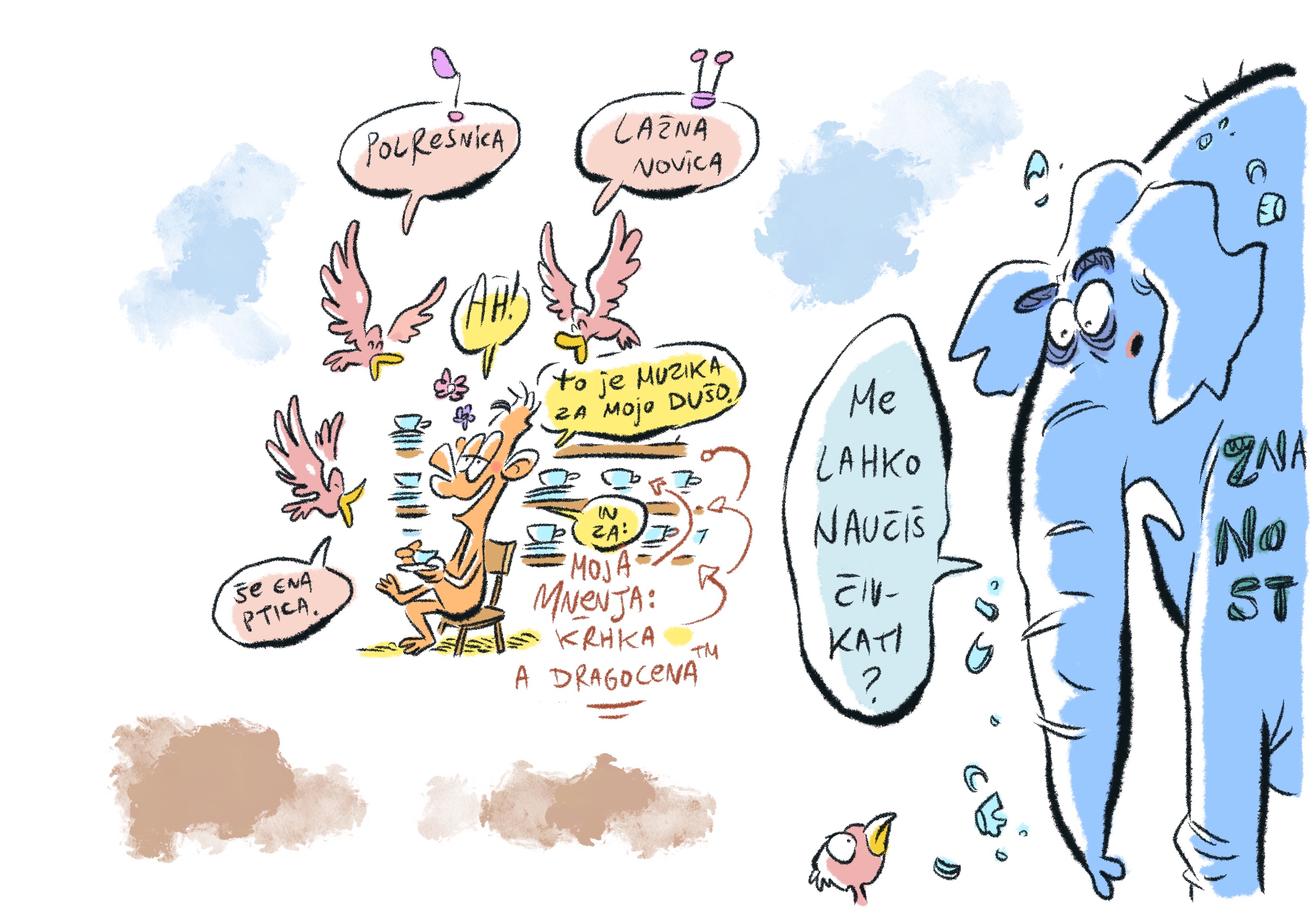

Professor Balthazar's inventions are consistently designed to help others: humans, animals, and even aliens, the latter being interpreted as representing diversity and inclusivity. He is rarely motivated by personal gain but rather is driven by empathy and the desire to alleviate suffering. In this spirit, he comes up with contraptions such as "the melody-pede", a musical exercise bike to help an overweight policeman lose weight, and "a strange and wonderful firefighting device" to help clumsy local firemen do their work more safely and with more joy.

There is no indication that Balthazar seeks to profit financially from his inventions. The only indication of prosperity is his spacious townhouse filled with scientific equipment and laboratories, and his overseas travels. Balthazar's inventions and his entrepreneurial success are not linked to the accumulation of wealth but to societal benefit. There are many such inventions in the series, such as a giant air purifier, "smoggyex" that transforms pollution into free fuel for cigarette lighters, and ice skates for Axel the penguin so he can deliver mail when the postman is ill during a freezing cold winter. Even more whimsical innovations, such as the rainbow maker from Somewhat over the Rainbow?/Duga profesora Baltazara (Zaninović 1971) initially invented for a festival of beauty, gain full value only when repurposed for socially useful goals.

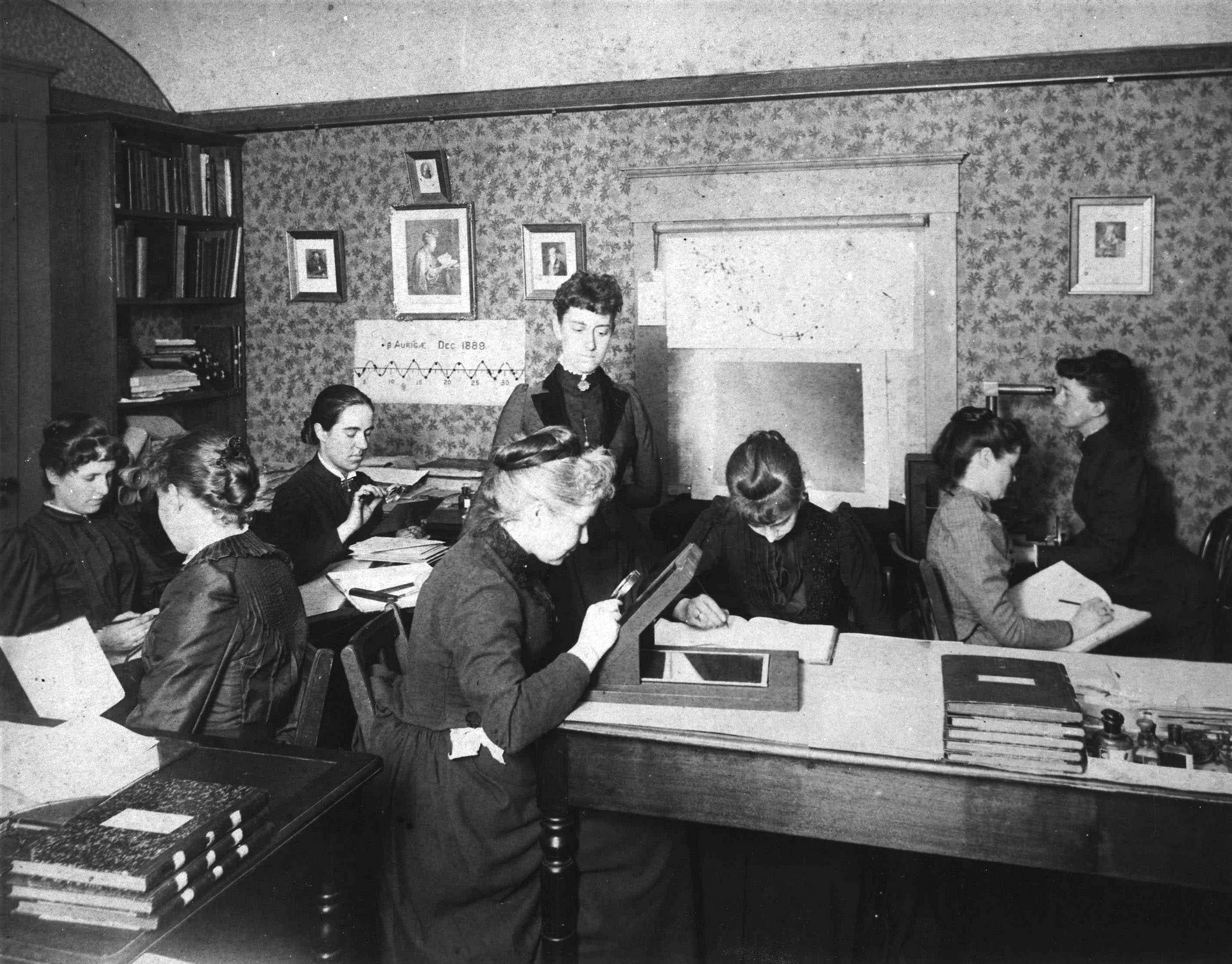

Balthazar's work consistently prioritizes ordinary people over elites or profit-driven entities. His research is determined by the needs of the community, evoking a participatory, citizen-oriented approach to science as well as socialist ideas about science. As such, he arguably takes science out of the much-criticized ivory tower and into the wider world.

Balthazar actively engages with his inventions, combining hands-on tinkering with creative problem-solving. For instance, in Somewhat over the Rainbow? he uses a screwdriver and hammer – tools that evoke the practical labour ethos of the era – to repurpose a device. In Dancing Willy/Hik! (Gašparović 1977), he produces and installs a tiny screw to repair a friend's car. This approach underscores that technology in Balthazartown is a tool to serve people, not a replacement for them. This aspect of the series is not surprising as the Zagreb School of Animated Film, influenced by the Yugoslav cultural context and the general ideological values of the time, frequently presented stories about the struggles of the ordinary person, the so-called "common man". Midhat Ajanović, a film scholar at the University West in Sweden, even argues that the cartoon creators that came out of the Zagreb school were loyal citizens of the socialist state and even its "ardent advocates". He adds that their cartoons often celebrated the so-called "Third Way", the idea that Yugoslavia, which was situated at the border of the capitalist "imperialist West" and the communist "bureaucratic East" during the Cold War, could plot its own alternative socio-political path to prosperity not being strictly aligned with either of the two blocs while taking the best aspects from both. Yugoslav President Josip Broz Tito, having established the international Non-aligned Movement in Belgrade in 1961, was the central figure of this political project. Given the stability and economic prosperity in Yugoslavia at the time, Ajanović notes that the Third Way was extremely popular among its people and artists.

Some academics have suggested parallels between Balthazartown and Yugoslavia, both being unusual societies struggling against the odds for their own survival in an unpredictable world. Ajanović (2000) notes that many characters created by the Zagreb School of Animated Film can be seen as symbols of "the idea of neutrality, independence and a big NO to bloc politics". The worlds created by this school celebrated the Yugoslav system as a "little oasis of freedom surrounded by pressures, terror and danger". During much of the Balthazar series, a sense of safety prevails as the professor is there to think of solutions to all problems and how to keep everyone safe – both in Balthazartown and on his travels abroad, such as his trip to London to lecture about the "use of fog for peaceful purposes". There are parallels here with President Tito navigating the tricky geopolitics of the Cold War and the looming threat of nuclear war to keep the country safe. This link between the cartoon and politics of the era is also noted by Paul W. Morton in his 2018 doctoral thesis at the University of Washington on the topic of Zagreb School of Animated Film, in which he suggests that Balthazar, a "gentle, eccentric inventor … who solves the problems of friends and neighbors, while also promoting world peace on the global stage", is effectively a "children's version of a Titoist diplomat and Third Way self-manager". Morton also notes that "Professor Balthazar's machine is always there to restore the Third Way project his town pursues".

The Zagreb School of Animated Film advocated a humanist vision of science and technology. Morton observes that the Balthazar series "sought not to technologize the human, but rather to humanize technology." Such efforts are evident in episodes where Balthazar modifies or creates technology to enhance human wellbeing, modernizing a craftsman's workshop to allow workers more rest (Bim Bam Bum/Bim i Bum, Grgić 1971) or designing a robot to assist a night watchman so he can sleep (The Night Watchman/Alfred noćni čuvar, Grgić 1971). Technology here is framed as liberating and life-enhancing rather than exploitative, with automation serving leisure, safety, and inclusion rather than cost-cutting or dehumanization.

The series also critically examines new technology that disregards human needs. In Steeples are Funny/Zvonko sa zvonika (Kolar 1971), a gentle humanoid worker with feelings who is in charge of a bell tower gets replaced by a heartless robot for efficiency purposes. But the new robot, depicted as a menacing, sad-faced mechanical cog personifying the dread of technological change, is insensitive to living creatures. "A simple image…can express more than many words", notes filmmaker Luigi Scarpa, who studied the series for his graduate research. The people of Balthazartown become miserable as a result of this intervention, and eventually decide to go back to more humane technology. So, there is nuance here with a humanist and socialist outlook: not all automation is seen as bad. Instead, the true value of technology derives from how and why it is used, and what happens to the worker as a result. Money doesn’t even enter the equation. Today the ethics of automation and its impact on the workforce remain an active field of research and public debate. Thus Balthazar remains relevant.

Humanism and Hope in Balthazartown

Suspicion of how and why the results of research and new technology are deployed is a theme in the final episode of the original series (An Endless Deviltry/Zrak, Grgić 1977) where the mass production of Balthazar's pollution filter in search of profits leads to further environmental harm, recreating and worsening the original problem. The failure of Balthazar's invention to fully resolve the issue highlights the limitations of individual solutions within a broader systemic context. Balthazar is a "controller" as Morton (2018) puts it, but "his control is limited". Scarpa interprets this as being the main message of the series as a whole; that even Balthazar can only influence the wider reality to a certain extent, and that the education and civic responsibility of all people is what is ultimately needed to preserve the natural environment and humanity.

The need for education and active civic duty seen in the final episode of 1977 is also emerging as a key topic of the latest series, which is now being produced along with a computer game in which the individual player's thinking and skills take on some of the responsibility for what happens in Balthazartown. Despite both of these iterations being made more than a half a century after in a different socio-political system, Balthazar's core values of humanism and focus on using science and innovation to benefit his community remain relevant.

Rather than promoting a clear-cut ideological message, the series as a whole presents a nuanced vision of science and technology as tools that can support communal wellbeing, provided they are used ethically and inclusively. It avoids simplistic binaries and instead foregrounds the role of the inventor as a socially-embedded figure – collaborative, empathetic, and attuned to the needs of the many.

Balthazar's enduring appeal likely stems from this combination of imaginative storytelling, social responsibility, and optimism about human ingenuity. While inspired by a specific historical and political context, the series' core message – about the value of using knowledge and skills for the common good – resonates beyond its original setting and continues to offer insights today.